Kundera's Mask

Two of the our recently published novels have much in common in spite of their very different cultural contexts – or at least so they were felt to be at the time. In fact they came from two worlds sealed off from each other.

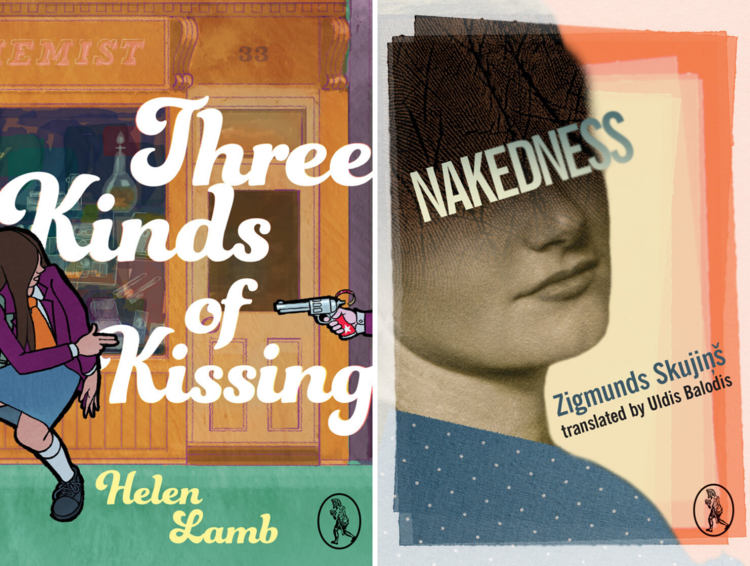

Three Kinds of Kissing, Helen Lamb’s beautifully crafted and deceptively insightful novel set in Britain of the late sixties and early seventies, deals with the secrets and lies of teenagers surrounded by a satisfyingly dysfunctional adult world that provides most of the humour. Skujiņš’s stylish and witty Nakedness, set in late sixties Latvia also speaks of adolescent delusions, but his principal characters are four or five years older.

Both novels observe human behaviour in a manner that makes you think, “Yes, that’s what people do,” or “Yes, that’s was how we lived.” It’s remarkable how the then Soviet youths resemble those of my own late-teenage years – down to the desultory pop group.

Both novels have a key secret whose eventual revelation at the end of the book explains everything that went before, though Nakedness implies that something doesn’t add up from the very first page, creating the sense of mystery that pervades the book, while Lamb takes the road to tragedy more slowly, the consequence of apparently innocent and even playful mendacity arising from the anguish and insecurities of adolescence.

Milan Kundera wrote in one of his novel (I confess that I cannot remember which) that teenagers try on different masks until they find one that fits (though it is still a mask!). He must have been writing at more or less the same time as the one in which these novels are set, but he would have been viewing late adolescence from the privileged position of a middle-age man, as did Skujiņš. Whether they were asserting this idea on the basis of their own experience or on observation of the time they were writing in, I cannot say, whilst Lamb was writing from a greater distance about a time and place she experienced in her own youth. Does this experimentalism assisted by the imagination of Billy Liar belong exclusively to Lamb’s generation or is it a perennial condition of adolescence? And am I the right person to answer this question, given that I come from the generation we speak of. It is a sign of provincialism, including generational provincialism, to think that one’s own experience of this life reflects the natural order – that everyone is like us, which is partially true but not entirely.

In the thirties, despite the depression, there were the first signs of a semi-independent youth generation who with low outgoings and some kind of employment had a little disposable income. In this capitalist society, this meant that they had a presence, albeit a marginal one. After the war, this trend flourished and independence became more marked. Youth culture was created, disturbing the older generations in the sixties with the length of the boys’ hair and the shortness of the girls’ skirts. Such innocuous things were accompanied by more serious challenges, which proved however to be more playful than genuinely serious, even when they were violent. I refer to May 1968 and the revolution that never was, though in truth some significant political advances were made in Portugal (somewhat later) and Italy (the following year).

Ours was the generation that wagged its moralistic finger at our parents and then turned out to be worse than them. It discarded reforms that it had benefitted from. It was a generation of immense self-confidence that grew up with increasing affluence and whatever good instincts it may have had dissolved in these last four decades of greed, spending yesterday’s money (in the form of state assets rebuilt out the ruins of war) and tomorrow’s (by inventing weird financial instruments to delay the payment of new assets). It is very interesting then to look at this generation in its youth and be reminded of the innocence and hope that forms only the background to the personal tragedies that dominate these two books. These societies were, as those who were there can remember, still communities and distances were much greater. National insecurities were almost unknown, and confidence in the future – and in progress, that concept we never really examined – was much greater.

These two novels, which Vagabond Voices has published, demonstrate in their parallels something that I have reflected on for many years: the difference between generations is greater than the difference between nations. Then the dictum only concerned European countries and their settler offspring; now it is global.

In 1970, small-town Britain and the archetypal small industrial town in the Soviet Socialist Republic of Latvia have a great deal in common. By this time the Soviet “Thaw” was well and truly over, Dubček’s brave attempt at reform had been crushed, and Brezhnev, the ultimate fool a gerontocracy could throw up, was doing all he could to ensure nothing of the kind would repeat itself. We now know that all his belligerence was in vain and his corrupt practices created a bizarre form of primitive capitalism that gave the elite the taste for more. Britain in the sixties, which according to the French political scientist, Jean Blondel, had the highest social mobility after the Soviet Union (now lost in both countries), was perhaps enjoying the greatest freedom of thought in its history. Of course the press was dominated by its barons, but TV, particularly ITV’s World in Action , was busy informing us. Most importantly, many of our teachers encouraged us to think independently – and once encouraged it often entered the blood. However, Britain was no utopia and still very much a capitalist country: it did what such countries do and reversed what progress had been made by attacking the unions with devious methods and increasing recourse to violent ones.

In 1970, both Britain and Latvia had better educational and health systems than they had had in the past, in spite of their far from perfect elites. There was full employment, and the working environment was more relaxed, particularly in the Soviet Union.

In the nineties, Latvia would regain its status as an independent nation, which was one of the few examples of good news in those years, whilst the post-Soviet Russia lurched through Yeltsin’s famine years in which life expectancy for men dropped from seventy-eight to fifty-eight. The post-war collectivist consciousness appeared to be dead and indeed it may still be. It may be impossible to resurrect.

Neither of these books were written as sociological documents and still less political ones, and to reduce them to such things would be to belittle them, though all novels are unwittingly also that, and this becomes clearer with the passing of time. The purpose of the novel is to challenge the reader to think about things differently and to do it by applying the author’s unique poetics. Neither book is challenging the governments of the day, but both are interested in presenting the reader with the tragic anguish of a particular stage in life which we all pass through and then almost completely forget. We are often dismissive of it, and both books remind that we shouldn’t be. The battles – often fought entirely in an individual’s head – are more courageous and heroic than those recounted in famous epics of the past.

Allan Cameron

If you want to buy both books together, you can do so for £14.00 (no delivery change within the UK) here.